For many years, mercury was the chemical of choice for artisanal miners extracting gold in Kenya. Today, sodium cyanide is increasingly being used to process gold-bearing ore – a trend seen around the world in what has been described as a ‘cyanide revolution’.

However, criminality and corruption in Kenya’s gold sector have left authorities struggling to regulate this potentially lethal chemical and contain its environmental impacts. The research for this piece was based in Migori, Narok, Siaya and Kakamega counties, and Nairobi, in September 2021.

A Kenyan government official collected a water sample in Kowuor village, Migori county, September 2021. Residents believed that the sudden deaths of several livestock could be linked to a nearby gold-leaching site and the use of Sodium Cyanide.

The shift to Sodium cyanide

Sodium cyanide is more efficient in processing lower-grade gold ore than mercury is. Using mercury can get between 25% and 50%, maximum 60% of gold, but with cyanide, one can get 95% or even 100% of gold from ore. This means that piled ‘tailing’ from gold extraction – ongoing in Kenya since the colonial period – is a proverbial gold mine and a magnet for firms wanting to perform gold ‘leaching’, the process of extracting gold from this waste product.

However, many of these leaching sites operate illegally. Where there is enough tailing to sustain a leaching site, people often build one quickly, work on tailing from an area for six months to a year. Once the area is exhausted, they move on to the next area. This avoids government inspection… most [sites] are illegal. That is why there are leaching sites in urban centres to complete the process from illegal sites.

Sometimes the authorities are only alerted that a site is in place once the operators have moved on after finishing the tailing in the area. It becomes harder to start looking into how cyanide can be decommissioned when there are no legal persons [who can be traced and held responsible].

Yet the health of local communities and their livestock is put at risk if the strict protocols necessary to ensure that sodium cyanide is used safely are ignored, as the chemical can contaminate water sources. Many of the temporary leaching sites described have been the cause of environmental damage, as they are left untreated. However, by this point, the leaching groups have moved onto other sites, leaving no means for residents to hold them accountable.

Previously, there were efforts to control mercury in the gold-mining sector, especially due to artisanal and small-scale [mining’s] effects on the environment. Then sodium cyanide came in and its impact [on health] is more rapid.

Opaque ownership and licensing problems

Most investors who run illegal leaching sites accuse the authorities of rendering it impossible for them to operate legally, due to delays in the approval of licences for leaching sites, in addition to corruption and political interference. Obtaining a licence can take up to two years – even though the sites themselves may take mere months to clear. For example, Migori county reportedly had 10 official licensed sites yet 40 applications awaiting approval as of September 2021. Most sites operating in the region are illegal.

There is a lack of resources in the relevant departments. For example, just a few officers from the Department of Geology oversee Migori, Homa Bay, Kisii, Nyamira and Narok counties, which encompass a huge gold-mining region. This makes it difficult to identify and control leaching sites. In surveys, illegal sites are often found. Authorities often give the operators time to apply [for a licence] or close them and rely on police to effect these orders.

This situation renders the ownership and management of leaching sites opaque to surrounding communities: often the names of the companies, directors or ultimate ownership of sites are unknown. There are few local workers – much of the skilled labour is provided by workers from overseas – and they are often paid in cash, leaving a scant paper trail. Most locals name a site after the majority group of the foreign nationals working there, which can often be Tanzanian, Indian or Chinese nationals.

Corruption and violence in the gold sector

People in the industry claim that political figures are often the ultimate beneficiaries of the business. In September 2019. an operation by authorities in Migori county led to the closure of over 40 gold-mining and processing plants operating illegally, including two reportedly controlled by a high - level county official. This is allegedly indicative of the industry today.

A law firm clerk said that most leaching sites are run by people with political connections, which allows processes to be sidestepped when drawing up agreements and buying land. A year ago, a land sale agreement was done by some Indian traders through a company that was buying land locally. When the clerk protested that it could be illegal to include gold leaching as a prospect for what they would do in the land, they insisted the agreement would sail through because they were backed by senior government officials. Sure enough, six months later a leaching plant was up and running.

Operating outside the legal system has also left leaching sites at a higher risk of conflict, as disputes over gold deals and rivalries between businesspeople are manifested through violence rather than the courts.

One such incident took place on 18 March 2021. when armed men wearing General Service Unit (Kenyan paramilitary police) uniforms attacked a gold-leaching site in Isebania, close to the Tanzanian border. Part of the raid was captured on CCTV phone footage at the premises of a businessman, who claimed that the officers stole 2.5 kilograms of gold worth 11 million Kenyan shillings (Ksh) as well as Ksh2 million in cash (approximately US$95 000 and US$17 000. respectively).

Arriving in unmarked Toyota Land Cruisers, the police moved to the leaching site and forced their way through by jumping over the gate, beating up three workers and briefly abducting two others. They tortured the men and forced their way into a safe house. They then proceeded into a nearby bar owned by the same trader, started beating up patrons further, then left.

The advocate representing the businessman said that neither the police in Migori nor at the nearby Isebania police post were aware of the raid and that they would pursue the case with the government. The businessman was later charged for tax evasion by the Kenya Revenue Authority in the Kisii High Court. He wished to know how much tax he owed the government or what law he had broken to allow this kind of attack from paramilitary [troops] and not regular police, who came in without a search warrant or bothered to tell him what happened. He was charged in court, but nothing was yet clear. Since the attack, the businessman has lost clients, business partners and trust; he has been forced to close down the site and has greatly scaled down on gold investment.

Again, there is a suggestion that this is politically linked. Sources familiar with the leaching site (speaking on condition of anonymity) said that it has been used as a front by senior Migori county government officials and local politicians. The raid may have been the result of a disagreement between these parties, as local government were unaware it would take place, suggesting that the order for the raid came from higher up.

The risk of violence – in disputes between business rivals or corrupt authorities – has shaped how leaching sites operate. For security, people often use urban centres for either leaching or finalizing the process of purifying gold from leaching sites, because in rural areas, getting attacked by criminals is easier. Most urban sites have high brick-and-mortar perimeter walls, razor or live wire on top and several gates and sections cordoned off for security.

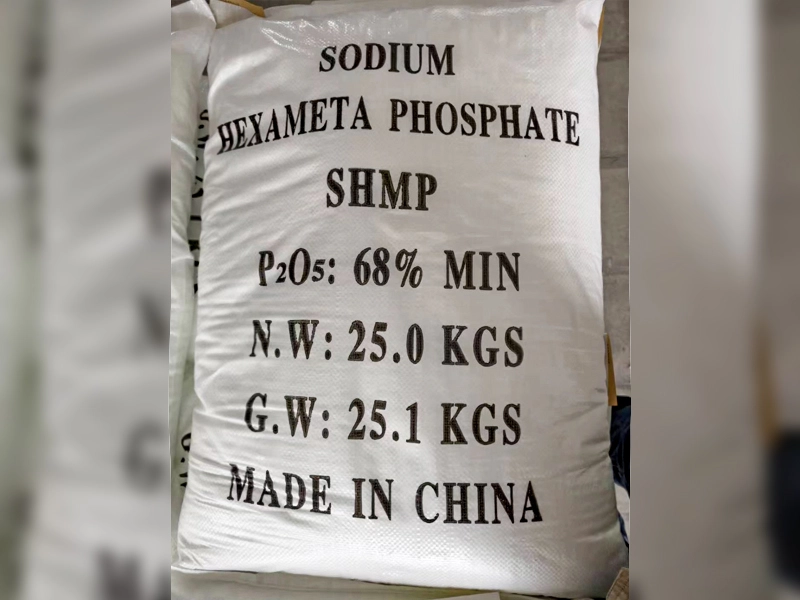

Cyanide supply chains

All those in the leaching industry reported that sodium cyanide is rarely bought in Kenya, because of strict regulations around its handling and transport. For example, under Kenyan law, cyanide must be transported in an openly marked vehicle showing its contents, which attracts unwanted attention to leaching sites that are operating illegally.

Instead, the chemical is often smuggled in from Tanzania. Tanzanians have a chokehold control on cyanide, mercury and sulphuric acid routes in gold mining in Kenya; they have managed to evade all taxes to be paid [by using] smuggling routes… a tonne of cyanide is between Ksh400 000 and Ksh500 000 [US$3 400–US$4 300], and it has remained steady for a long time. Some have tried to import the chemicals from Uganda… where they have gold interests, [but] taxes and dealing with government places a tonne of cyanide at Ksh600 000–Ksh700 000 [US$5 100–US$6 000], with more costs incurred when transported openly in Kenya.

Once the chemical is bought in Tanzania, it is transferred to smaller sealed tanks of about 120–200 litres across the border. People strictly use minivans with tinted windows to transport the chemicals through smuggling routes. Minivans – as opposed to the trucks used to smuggle other products – are chosen because the substance is poisonous and must be handled carefully.

The geology officer of Migori county also confirmed that most sodium cyanide and the skills to use it come from nearby Tanzania, where it has been in use for a long time. This reliance on Tanzanian supply chains means that many sites in Kenya are Tanzanian-controlled.

The risk of an opportunity missed?

The ‘cyanide revolution’ could be a golden opportunity for Kenya’s mining sector, allowing businesses to make profitable use of what is otherwise simply a waste product. However, criminality in the sector, vested political interests and the use of violence are instead turning this opportunity into a risk.

The police commander, environment agency officer and geology officer in Migori county all agree that an effort across Kenyan government departments to control leaching and cyanide use is the best strategy for bringing stability to the sector. The police can arrest, but they need experts from other departments to ensure an all-round operation that will help in court cases.

In the meantime, as long as these toxic substances are being used by groups operating outside the law, the health of Kenyan communities and livestock is being put at risk.

Disclaimer

This article is reposted from the Internet. The content is for reference only, and we do not claim any ownership or original creation of it. We are not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, or reliability of the information in the article. If there are any issues regarding copyright or other legal concerns, please contact us, and we will take appropriate actions promptly.

- Random Content

- Hot content

- Hot review content

- Copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate 98% Grade

- အလုပ် ခေါင်းစဉ် : ပြောင်းသာလဲသာ ရှိ သော ဖောက်သည် နှင့် ထောက်ပံ့ ပေး သူ ဆက်ဆံရေး ကျွမ်းကျင် သူMyanmar

- Potassium Permanganate – Industrial Grade

- calcium chloride anhydrous for food

- Triethanolamine(TEA)

- Maleic Anhydride - MA

- Cupric Chloride 98%

- 1Discounted Sodium Cyanide (CAS: 143-33-9) for Mining - High Quality & Competitive Pricing

- 2Sodium Cyanide 98% CAS 143-33-9 gold dressing agent Essential for Mining and Chemical Industries

- 3China's New Regulations on Sodium Cyanide Exports and Guidance for International Buyers

- 4International Cyanide(Sodium cyanide) Management Code - Gold Mine Acceptance Standards

- 5China factory Sulfuric Acid 98%

- 6Anhydrous Oxalic acid 99.6% Industrial Grade

- 7Soda Ash Dense / Light 99.2% Sodium Carbonate Washing Soda

- 1Sodium Cyanide 98% CAS 143-33-9 gold dressing agent Essential for Mining and Chemical Industries

- 2High Purity · Stable Performance · Higher Recovery — sodium cyanide for modern gold leaching

- 3Sodium Cyanide 98%+ CAS 143-33-9

- 4Sodium Hydroxide,Caustic Soda Flakes,Caustic Soda Pearls 96%-99%

- 5Nutritional Supplements Food Addictive Sarcosine 99% min

- 6Sodium Cyanide Import Regulations & Compliance – Ensuring Safe and Compliant Importation in Peru

- 7United Chemical's Research Team Demonstrates Authority Through Data-Driven Insights

Online message consultation

Add comment: